Exploring Quantum Materials with Scanning SQUID Microscopy

Nowack Lab, led by Associate Professor Katja Nowack at Cornell University, focuses on using experimental physics techniques to explore emergent and interesting phenomena in novel materials, often referred to as quantum materials. Working in the field of condensed matter physics, the lab’s primary research tool is scanning SQUID microscopy.

Situated at the Physical Sciences Building, the team’s lab is the setting for experiments in a wide range of subjects, from unconventional superconductors and topological materials to the flux trapping properties of superconducting films and structures.

In this case story, we explore how the team seeks to understand quantum materials, the techniques they use, and how cryogenic measurement systems from Bluefors are essential in this work. You can also watch an interview with Katja Nowack, produced in collaboration with The Quantum Insider.

Scanning SQUID Microscopy

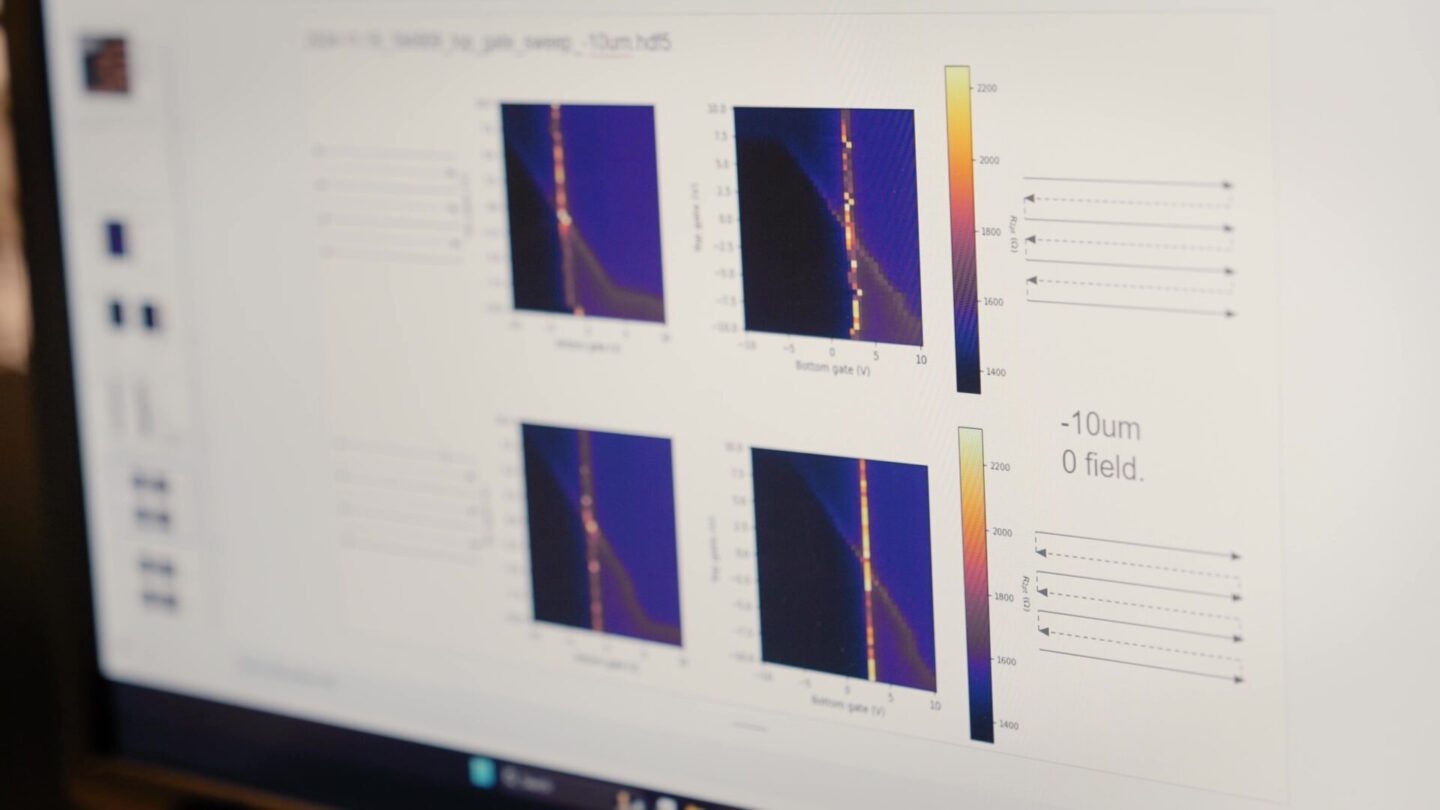

The primary research tool of the Nowack Lab is scanning SQUID microscopy. This technique involves using superconducting quantum interference devices (SQUIDs) – minute sensors that are sensitive to changes in magnetic flux – to perform magnetic imaging. In this technique, the sensor is positioned close to the surface of a material under study for imaging, allowing the researchers to take detailed images of the stray magnetic fields emanating from the materials.

One vital feature of this technique is its high sensitivity. The images capture detail at the micrometer scale, making them ideal for studying subtle quantum phenomena that are not easily detectable using other methods.

One of the materials the lab investigates are unconventional superconductors. Using scanning SQUID microscopy, the team aims to understand the mechanisms behind superconductivity in these materials. While we understand how superconductivity occurs in many materials, there are also many unanswered questions.

“There’s a lot of superconductors, called unconventional superconductors, where we don’t know the details of what this quantum state actually looks like, and we also have a very hard time understanding why the material might be superconducting. And so those are the kind of materials that we study with our technique,” Nowack explains.

Wide Range of Quantum Materials Research

Scanning SQUID microscopy is a very versatile technique, facilitating the exploration of a broad range of phenomena. Another area the group studies is topological phases of matter.

Topological materials exhibit unique electronic properties due to their band structure. There are still many questions about how current flows in these materials, which can be studied with the technique. Magnetic imaging can help visualize the current flow, as the current produces a magnetic field that can be imaged. For example, one significant discovery the group made involved imaging quantum anomalous Hall insulators.

“If you look at the literature of the quantum anomalous Hall effect, it will always say the current is going to flow along the edges or through chiral edge modes in this material. And we set out to image exactly that. We thought it would be a cute experiment – like we’ll see the current flow along the edges and it’s going to be great. We’ll just confirm what everybody has been saying,” Katja explained.

When the group started doing their experiments, they started getting data that showed the current instead flowed through the interior of the devices, challenging long-standing assumptions.

“That puzzled us for a long time. But then we went back into much older literature about the so-called quantum Hall effect and found that it had actually been debated for a long time whether the current truly does flow along the edges, or if it might actually be in the bulk, or maybe even be kind of coexistent in the bulk and along the edges. So, this is not at all a closed book at this point,” Katja says.

In the published work, the team imaged two samples from two differently-fabricated thin films. Based on this experiment, the group can now investigate how these materials generally behave.

“It’s actually a starting point for us to look at more samples, look at variations of this state of matter, and see if what we’ve observed is now really the generic behavior of the current distribution, or if maybe each sample is its own beast, which sometimes also happens with materials,” she says.

Applications in Information Technology

The research the Nowack Lab is making on quantum materials might have implications for future applications in information technology. Unconventional superconductors or topological materials might for example be useful in developing more efficient electronics, or advancing devices used in quantum computing.

“Some of the research is really just fundamental. The phenomena are very amazing and interesting to study,” Katja says. “However, with a lot of these materials, if they’re mature and we can really understand and control what they’re doing, there might be implications for information technology. That can be both for classical information technology and for quantum information technology as well. Those are typically the areas where future applications of these electronic phenomena might lie.”

Another area of interest for the lab is the flux trapping properties of superconducting films and structures. Developments in these types of materials can contribute to Superconducting Digital (SCD) electronics, which have been identified as a possible technology to improve the energy efficiency of computing in large-scale data centers. With this type of applied project, the research carried out by the team can prove useful for other research groups that are developing superconducting digital logic circuits.

“The idea is to build a classical computing chip based on so-called Josephson junction-based logic. There are challenges in those circuits with magnetic flux getting trapped in uncontrolled places,” Katja explains. “We’re trying to understand flux trapping properties of superconducting films and superconducting structures, to support the research groups that work on making this superconducting digital logic reality by helping them to come up with strategies to track flux in controlled places.”

Katja adds that this work might also aid researchers in quantum information science: “I’m hoping that that will also bring us in touch with quantum information technology eventually again, because I think the questions we are answering are also very relevant to superconducting quantum circuits.”

Cryogenic Measurement Systems from Bluefors

The study of subtle quantum phenomena requires an environment that is as noise-free as possible. To achieve this, cryogenic systems – such as the Bluefors LD400 dilution refrigerator used by the lab – are vital. They enable the lab to reach temperatures as low as 10 millikelvin at which the materials can be studied. The SQUIDs themselves are also superconducting sensors and need to be cold to function, but they only need temperatures of around 5 Kelvin or lower.

“The emergent phenomena we are interested in is typically collective phenomena of the electronic degree of freedom in the materials we study. And for those phenomena to really come to life and to come out, you have to quiet down the electrons,” Katja explains. “If the electrons are warm, if they’re hot, they have a lot of thermally excited motion. And you need to quiet all those excitations down to bring out these emergent phenomena that we find interesting. And so that’s why we work at low temperature.”

The cryogen-free cryostats used by the lab utilize pulse tube cryocoolers to achieve low temperatures without the need for liquid helium, making it simpler to operate at low temperatures.

“When I was a graduate student, I had to come in every 40 hours throughout Graduate School and do a helium transfer. Very tedious,” she remembers. “My students are completely free of this because, you know, it’s like you close up the system, you push a button, and it essentially cools down by itself and needs almost no maintenance.”

Cryogen-free dilution refrigerators also provide significant benefits for magnetic imaging, as they enable the systems to stay cold for long periods of time, providing a stable environment for hours of imaging. Katja mentions that this aids the imaging process with certain materials: “This is great because if you look at something that gives us very weak signals, we might need to take an image for even 48 hours.”

The first system the lab installed from Bluefors was an LD400 in 2016. It has proven to be a key tool for the team in their research, and the extensive support Bluefors provides has been much appreciated. “If we do run into trouble, we typically shoot an email and get a response really quickly to help us troubleshoot the system. That’s happened since 2016 and is still the case,” Katja says.

The lab also recently had a new system installed, an SDHe System, a continuous helium flow system with a base temperature of around 1 Kelvin. This new system utilizes the recently released Gas Handling System Generation 2, which, with its new hardware and advanced software, further enhances the ease-of-use and reliability of these cryogenic measurement systems.

When asked about the benefits, Katja compares its usability with the previous generation: “The new Gas Handling System also comes with a whole new software suite, making the control of the system even easier. It already was a very close to being a push button kind of system, and that has become even easier.”

Future of Magnetic Imaging

The Nowack Lab’s research shows the wide range of possibilities that scanning SQUID microscopy enables to make significant strides in understanding and harnessing the unique properties of quantum materials.

“I think just generally, the future for magnetic imaging is very bright. I think there’s a lot of room for studying phenomena on the local scale. There’s a lot of different local probes that you can use. I think magnetic imaging is really versatile at looking at these phenomena many different ways. I’m really looking forward to keep applying it to quantum materials,” Katja says.

In their work, the Nowack Lab is pushing the frontiers of magnetic imaging and the probes used. The team is working to develop new scanning probes, specifically nano-scale SQUIDs, for higher spatial resolution and imaging in applied magnetic fields. These new types of sensors could be produced in higher quantities, making them available to many more research groups and giving researchers better tools to study quantum materials.

“We’re trying to make these nanoscale SQUID sensors, and one aspect I am excited about is that we aim to do this on the wafer scale. Our vision is to make these SQUIDs kind of batch fabricated,” Katja explains. “If we can make these SQUIDs on a wafer scale, then maybe we can share them and more people will start doing magnetic imaging. That would be wonderful.”

Find out more about the Bluefors LD system and our next generation Gas Handling System.